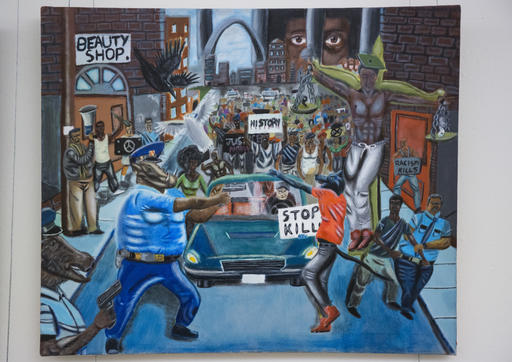

A controversy ensued over a high school student’s painting (pictured above) that was removed from the Capitol Building in 2017 because it had anti-police themes and offended some members of Congress. The student artist, David Pulphus, and the representative who supported the painting challenged the removal in federal court. However, a federal district court judge in Pulphus v. Ayers (D.D.C. 2017) ruled that the art display was a form of government speech largely because the government retained the ability to exercise editorial control over which paintings were displayed. (AP Photo/Zach Gibson, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

In drafting the Constitution, the framers acknowledged the importance of artistic expression, going so far as to define promotion of the “useful arts” as one of government’s purposes.

Despite this early recognition, artistic expression has historically been subject to some measure of direct or indirect censorship in the United States.

The First Amendment provides significant protection to artistic expression and, as a result, severely limits the government’s right to censor controversial works in most contexts. Nonetheless, restrictions on the publication of art continues in several contexts.

The scope of protection afforded to artistic expression largely depends on the nature of the speech. Artistic expression through the spoken or written word, particularly in the form of political protest or satirical speeches or writings, such as plays or stories, is akin to “pure speech”and is entitled to comprehensive protection.

By contrast, art created for commercial purposes or not designed to convey an expressive message (such as nude dancing) is entitled to less protection.

Some artistic expression is subject to censorship based on its content.

For example, “obscene” materials may be censored. Legitimate artistic expressions are never, however, considered obscene because in Miller v. California (1973) the Supreme Court excluded materials with “serious artistic value” from the definition of obscenity.

“Indecent” works, which are less than obscene but make use of patently offensive terms to describe sexuality or bodily functions, may be restricted. In Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), the Court held that indecent material, particularly in the context of television or radio broadcasts, which cannot be banned entirely under the First Amendment, may be restricted to avoid broadcast during times when children might typically view or hear it.

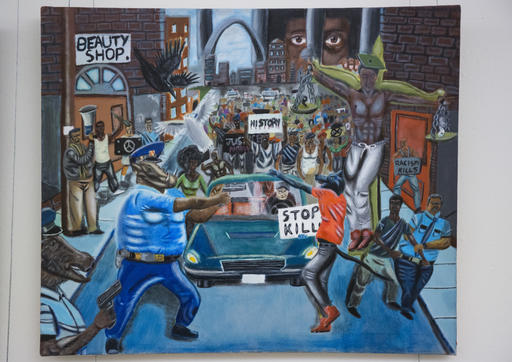

The maxim against prior restraint prohibits federal, state, and local governments from requiring a person to seek permission before publishing or speaking. Prior restraints have, however, been upheld in some limited forms. For example, courts have held that requiring a movie producer to submit a film for rating prior to showing it publicly is a constitutional exercise of government power despite the strong presumption against the legality of prior restraints. In this 1946 photo, films are getting a sharp going-over at the hands of 77-year-old Lloyd T. Binford, chairman of Memphis, Tennessee, movie board. He has banned half dozen popular films and whittled others down to what he considers “proper taste.” As a result, he has been the object of editorial and cartoon comment from coast to coast and has been threatened with a suit by at least one Hollywood producer. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Artistic expressions that are neither obscene nor indecent may also be censored because they offend the rights of others.

For example, defamatory works — those that maliciously harm a person’s character through falsehoods — fall outside the scope of the First Amendment and may be censored.

By contrast, the First Amendment does protect obvious satire of a public figure, so such expressions are not subject to censorship. In addition, artistic expressions that break various statutory laws, such as artistic renderings of currency that violate anti-counterfeiting law or works that offend copyright laws, may also be subject to censorship.

The maxim against prior restraint prohibits federal, state, and local governments from requiring a person to seek permission before publishing or speaking.

The rationale for placing a heavy burden on the government in this regard is that a ruling denying the right to exhibit or publish a work of art prior to its publication amounts to censorship. In light of this reasoning, attempts by the government to limit expression through prior restraint have largely been unsuccessful.

Prior restraints have, however, been upheld in some limited forms. For example, courts have held that requiring a movie producer to submit a film for rating prior to showing it publicly is a constitutional exercise of government power despite the strong presumption against the legality of prior restraints.

Controversy sometimes arises when publicly owned space is used for exhibitions or communication of art. The degree to which the government may censor such expression depends on the nature of the public space. In this photo, Art Academy students demonstrate outside the Hamilton County Courthouse in Cincinnati, Ohio, on September 24, 1990, as jury selection began in the obscenity charges against the Contemporary Arts Center for exhibiting photographs by late artist Robert Mapplethorpe. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Controversy sometimes arises when publicly owned space is used for exhibitions or communication of art. The degree to which the government may censor such expression depends on the nature of the public space.

In traditionally public spaces set aside for the exchange of ideas, like public parks, the government may not completely ban artistic expression unless it has a compelling interest that cannot be accomplished through less restrictive means. The government may, however, enforce reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions, such as requiring performances to take place within certain hours or limiting the size of the audience for purposes of public safety. In the event the government does enforce time, place, and manner restrictions, these elements must be viewpoint neutral and may not censor one opinion and favor another.

A designated public forum is one that the government has made available for public expression, but has not been traditionally set aside for the free exchange of ideas.

For example, a city hall allowing an art exhibit has been held to be a designated public forum. In this context, the government may censor artistic expression based on content only to the extent that such restriction preserves the purpose of the place. Thus, a city hall art exhibition could allow for quiet performances, yet restrict raucous musical groups from performing.

The government may completely censor expression in a nonpublic forum, such as a military facility or a mayor’s private office. Even in nonpublic spaces, the restrictions must be reasonable and not an effort to suppress a specific viewpoint while allowing for the expression of others.

Funding is one way the government can indirectly censor art. In National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley (1998), the Supreme Court ruled that the government need not subsidize art it considers indecent. Although Finley does not stand for the proposition that disagreeable art is subject to censorship, it does mean that the government need not sponsor art it finds offensive. In this photo, Performance artist Karen Finley talks to reporters outside the Supreme Court in 1998. (AP Photo/William Philpott, used with permission from the Associated Press)

To the extent that the government funds the arts, it may indirectly censor artists by refusing to finance projects.

The federal government did not become significantly involved with sponsoring the arts until it created the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) in 1965. In the 1980s, the NEA sparked a public and political uproar when it helped fund exhibits with controversial themes.

Critics accused the NEA of financing obscenity, and Congress passed an arts funding law in 1990 requiring that public values be considered in awarding grants. The Supreme Court upheld that law in 1998, ruling in National Endowment for the Arts v. Finley (1998) that the government need not subsidize art it considers indecent.

Although Finley does not stand for the proposition that disagreeable art is subject to censorship, it does mean that the government need not sponsor art it finds offensive.

Similar to the Finley case, government officials sometimes invoke the government speech doctrine in art display cases.

For example, a controversy ensued over a high school student’s painting that was removing from the Capitol Building, because it had anti-police themes and offended some members of Congress.

The student artist and the representative who supported the painting challenged the removal in federal court. However, a federal district court judge in Pulphus v. Ayers (D.D.C. 2017) ruled that the art display was a form of government speech largely because the government retained the ability to exercise editorial control over which paintings were displayed.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Gabe Teninbaum is the Assistant Dean for Innovation, Strategic Initiatives and Distance Education, as well as a Professor of Legal Writing, at Suffolk University Law School. Among other responsibilities, he leads the #1 ranked legal tech program in the nation, as ranked by National Jurist Magazine. He has taught more than 10 different courses and published more than 30 law review pieces and other articles.